Note: This post was published in October 2025 as part of a new web design but the work was completed in Summer 2024

Background

The language used to describe autism and autistic people both reflects and influences the way people think about autism. Language can be offensive and stigmatising, or respectful and empowering. Autistic led organisation Aucademy and blog posts by autistic people like this one have identified or described language preferences. However, as some journal articles have found, there is no universally agreed way to describe autism, even amongst autistic people and their supporters.

Language preferences can also change over time, and they can be different for different groups of people, for example in different countries or regions. To make sure the language we use is consistent with the current preferences of as many autistic people as possible we designed a survey to explore language preferences when describing autism.

How this work empowered people to make more of a difference:

This work was carried out in July 2024 and has been informing our communications ever since. By responding to this survey, autistic people were able to share their views about the language used to describe autism. Responses to this survey help our communications be more acceptable to more people. They also help us explain these preferences when we talk to others, encouraging more people to think about and to understand language preferences. This is an important part of decreasing the stigma around autism. By taking part, autistic people were therefore playing a role in societal change.

What did we ask people to do?

We emailed a survey link to all members of the Community Advisory Panel (at that time 647 people). They were asked to share their opinions on the language often used to describe autism.

191 people responded, with this including 146 autistic people. We know language preferences can differ between autistic people and parents/carers/supporters, so we reviewed responses from these groups separately. In this post, we will focus mostly on the responses from autistic people.

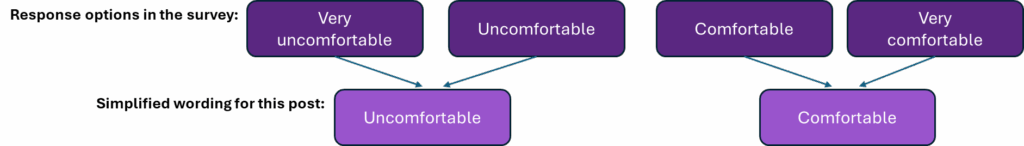

Note: To use as few words as possible, instead of referring to ‘parents, carers, and their supporters’, we refer to this group as ‘supporters’. We have also simplified how we refer to the response options that were used in the survey so that we simply refer to ‘uncomfortable’ and ‘comfortable’. The diagram below shows how these terms relate to the options from the survey:

How we used suggestions/responses:

We used the responses to identify language preferences when describing autism.

There were no surprises – our results are very consistent with what others have reported and reflect the language we already use, which is reassuring and suggests preferences about most of these words are not changing rapidly over time.

We will primarily use identity-first language (autistic person).

Autistic people, their supporters, and professionals have different preferences around using identity-first language (that puts a condition first e.g., ‘autistic person’) and person-first language (that puts the person first e.g., ‘person with autism’).

We will continue to use ‘autistic person’ in our communications, as 86% of autistic people in our survey were comfortable with this term (supporters = 80%), whereas only 42% of autistic people were comfortable with ‘person with autism’ (supporters = 46%).

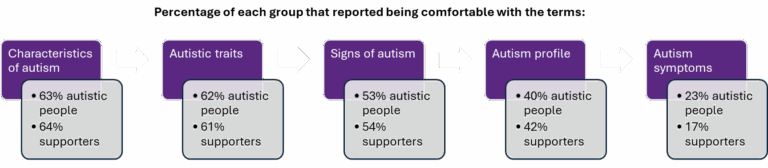

We will continue to say ‘characteristics of autism’ or ‘autistic traits’ rather than ‘symptoms’.

Although the autism diagnostic manual refers to ‘symptoms’, we found autistic people in this survey were more comfortable using other terms:

We will refer to the ‘autism community’, but be clear what we mean.

We often refer to autistic people and those who support them, such as parents and carers, but we wanted to find a shorter term we could use. We found that 61% of autistic people were comfortable with the term ‘autism community’ (supporters = 63%), but to be mindful of the 23% of autistic people who were uncomfortable with it, we will make sure it is clear what we mean by the term when we use it.

We have developed a short explanation to include alongside text where we use this term →

What do we mean by the ‘autism community’?

We use the term ‘autism community’ to describe anybody with a strong interest in – or connection to – autism. This includes autistic people, with and without a diagnosis, as well as parents, carers and other supporters. It also includes autistic and non-autistic people who work or volunteer in the area of autism, for example in health or social care roles, and researchers.

The word ‘community’ simply means we are referring to a group of people with a shared interest. It is not describing a joined-up community or a sense of community.

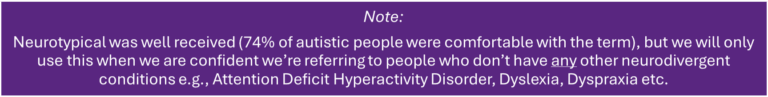

We will say ‘non-autistic’ if that’s what we mean, and only use ‘neurotypical’ if we really mean people with no neurodivergent conditions at all.

We tend to refer to non-autistic people in our work and wanted to see how comfortable people were with this compared to other options. Although only 46% of autistic people were comfortable with ‘non-autistic’ (supporters= 33%), we will continue to use this in our communications as fewer autistic people were uncomfortable with this term compared to alternatives like ‘allistic’ (39% uncomfortable), and ‘normal’ (82% uncomfortable).

We will not remove all mention of Asperger Syndrome, as we don’t want to exclude people who already had that diagnosis, but we will be clear it is not a currently used diagnosis.

The term Asperger Syndrome was removed from the diagnostic manual in 2013, but some people still have this diagnosis because they were diagnosed before it was taken out of use.

29% of autistic people (supporters = 26%) said they were uncomfortable with us not using this term, so in the future, when we ask about diagnosis, we will include Asperger Syndrome as an option. If we mention Asperger Syndrome in other communications, we will be respectful of those who still have the diagnosis, whilst being clear that it is no longer given as a diagnosis.

There might be times we seek further clarification from people with lived experience.

We looked at other general terms used to describe autism and found that the majority of autistic people were comfortable with: additional needs, disability, distress behaviours, masking, meltdown, shutdown, self-harming behaviours, stimming, neurodiverse, and neurodivergent. However, there were mixed findings for: challenging behaviour, low support needs, high support needs, and special needs and the majority of autistic people were uncomfortable with: disruptive behaviours, problem behaviours, high functioning, low functioning, mild autism, and severe autism.

We will use these findings to guide the language we use in our communications. Where specific pieces of work touch on areas where language is challenging or preferences unclear, we will seek further clarification from people with lived experience.

We also used the responses to understand whether members of the panel supported further work on language preferences and if a new language guide would be well-received.

Overall, there were mixed findings:

Some of the comments suggest that further work around language preferences is needed. For example, people commented that:

- Negative language is still used and this can make autistic people and their supporters feel ‘uncomfortable’.

- There are still some common stereotypes such as ‘everyone is on the spectrum’.

However, there were more comments explaining why we shouldn’t develop this piece of work further. As well as it being noted that other organisations have already created language guides, other comments were:

What's next?

As there was a lack of support to develop this piece of work further, we will be focusing on other priorities and not writing a new language guide at this time. If you would like further information on language preferences, based on research with autistic people and their supporters, you can download guidance from others, such as Aucademy and the community-led AIMS-2-TRIALS guide. Because opinions differ, both in terms of the guidance offered and the level of detail preferred, there is no one guide that everybody will be happy with. This means you may like one guide more than another.

Although we aren’t developing this work further, these results guide the language we use and have highlighted some of the sensitive terms, which we will take care to factor into our communications. Overall, we encourage respect for each other’s opinions and to always listen to how autistic people describe themselves, and ask them about their preferences where they are not clear.